Continuing Education Activity

A concussion is a “traumatically induced transient disturbance of brain function.” Concussions are a subset of the neurologic injuries known as traumatic brain injuries. Traumatic brain injuries have varying severity, ranging from mild, transient symptoms to extended periods of altered consciousness. Given the usually self-limited nature of symptoms associated with a concussion, the term mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) is often used interchangeably to refer to a concussion, though concussions are technically a subset of mTBIs. Prognosis is usually good, and most patients experience complete resolution of symptoms. This activity reviews the etiology, presentation, evaluation, and management of concussions and reviews the interprofessional team’s role in evaluating, diagnosing, and managing the condition.

Objectives:

-

Describe the various mechanisms of injury of concussions.

-

Review the relevant examination procedures for possible concussions, including labs and diagnostic imaging, where appropriate.

-

Discuss the management options for a patient with a concussion, especially regarding returning to sports activities.

-

Evaluate possible interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance the evaluation and treatment of concussions and improve outcomes.

Introduction

A concussion is a “traumatically induced transient disturbance of brain function.”[1] Concussions are a subset of the neurologic injuries known as traumatic brain injuries. Traumatic brain injuries have varying severity, ranging from mild, transient symptoms to extended periods of altered consciousness. Given the usually self-limited nature of symptoms associated with a concussion, the term mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) is often used interchangeably to refer to a concussion. However, concussions are technically a subset of mTBIs. Prognosis is usually good, and most patients experience complete resolution of symptoms.[1][2]

Etiology

A concussion occurs as a result of either a direct or indirect injury to the head. Providers often consider a direct, traumatic blow to the head as a significant cause of a concussion. However, indirect traumatic forces elsewhere in the body can lead to an acute acceleration/deceleration injury to the brain, which can also lead to a concussion.[2]

Epidemiology

In the United States, each year, there are an estimated 1.7 million traumatic brain injuries that prompt presentation to the emergency department.[3] The Center for Disease Control also estimates that when accounting for outpatient visits for TBIs and patients not seeking care for injuries, the actual incidence may range from 1.4 to 3.8 million concussions per year.[3] Frequent causes of concussions are motor vehicle crashes, being struck by an object, assault, and participation in recreational athletics. Although sports-related concussions make up a small percentage of overall concussions, much of the current research surrounding concussions stems from data on sports-related head injuries. Football consistently accounts for the highest number and percentage of athletics-related concussions in high school and college athletes. At the same time, soccer is responsible for the highest percentage of concussions in female athletes.[4] Female athletes suffer concussions about twice as often as male participants in the same sport.[4]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiologic mechanism of a concussion is complex. The acute symptoms of a concussion are due primarily to a “functional disturbance rather than structural injury.”[2] “Neurochemical and neurometabolic events” after an injury to the head result in an alteration of neurologic function.[5] Acceleration, deceleration, or rotation of the head result in acute axonal injury via disruption of neurofilament organization. The release of electrolytes through ion channel depolarization leads to a release of neurotransmitters and subsequent neurologic dysfunction. Changes to glucose metabolism decreased cerebral blood flow, and mitochondrial dysfunction also occurs.[5]

History and Physical

Assessment of a patient with a possible concussion should include gathering information on the mechanism of injury, the symptoms the patient is experiencing, the timing of symptom onset, and the severity and persistence of symptoms. The symptoms of a concussion can be wide-ranging but often fall into one of four main domains, which are listed below. Some of the most common symptoms seen with concussion within each domain include:

1. Affective/emotional function

-

Irritability

-

Changes in mood

2. Cognitive function

-

Confusion/disorientation

-

Amnesia

-

Mental fogginess

-

Difficulty concentrating

3. Physical/somatic symptoms

-

Headache

-

Dizziness

-

Difficulties with balance

-

Visual changes

4. Sleep

-

Drowsiness

-

Sleeping less than usual

-

Sleeping more than usual

-

Difficulty falling asleep

The Sideline Concussion Assessment Tool 5 (SCAT5) has a comprehensive inventory for possible symptoms of a concussion.[6]

Most patients (greater than 90%) diagnosed with a concussion do not have an associated loss of consciousness [7]; however, loss of consciousness is an important sign of a potentially serious head injury.[8] Additionally, the development of symptoms related to a concussion does not always occur immediately after an injury.[6] The development of symptoms within hours to days after a precipitating injury may still indicate a concussion.

Of particular importance in a patient’s history is whether the patient has a history of any prior concussions. “A greater number, severity, and duration of symptoms” with previous concussions can be predictive of longer recovery time.[1] Finally, pre-existing mood disorders, learning disorders, sleep disturbances, and migraine headaches may also impact the management of a concussion.[1]

A physical examination specific to concussions should include: [2][9]

-

Close examination of the head and neck area for any structural injuries

-

A thorough neurologic exam, including an assessment of strength, sensation, and reflexes; ocular assessment (including saccades and nystagmus); and assessment of a patient’s balance and vestibular system

-

Evaluation of a patient’s cognitive function, including formally assessing orientation and higher-level cognitive processing

-

An assessment of the patient’s emotional state, including a comparison of the patient’s current emotional state to their baseline with the patient’s family or friends if possible

Formal neuropsychological assessment by a trained neuropsychologist can supplement a clinician’s assessment of the multiple domains impacted by concussions.[2]

Evaluation

Diagnosis of a concussion remains an exclusively clinical diagnosis based on history and exam findings. However, there is no single pathognomonic finding or a minimum number of symptoms for diagnosing a concussion. Several standardized diagnostic tools can be employed in the pre-hospital setting following an acute head injury to assist in determining the presence of a concussion. The Sideline Concussion Assessment Tool 5 (SCAT5) is one of the most commonly used tools for a concussion assessment, particularly by athletic trainers and sports medicine providers to assess athletes on the sideline after a potential head injury. The Child SCAT-5 exists for the assessment of patients between 5 and 12 years of age.[10] The optimal setting for administering these tools is a quiet setting with minimization of surrounding distractions.[6] Monitoring for the development of symptoms or any signs of neurologic deterioration after the initial post-injury assessment is necessary because of the potentially delayed presentation of symptoms and objective findings.[11] Signs and symptoms including severe headaches, seizures, focal neurologic deficits, loss of consciousness, deterioration of mental status, and worsening symptoms may indicate a more serious head injury and should prompt referral to an emergency department for further evaluation.[2]

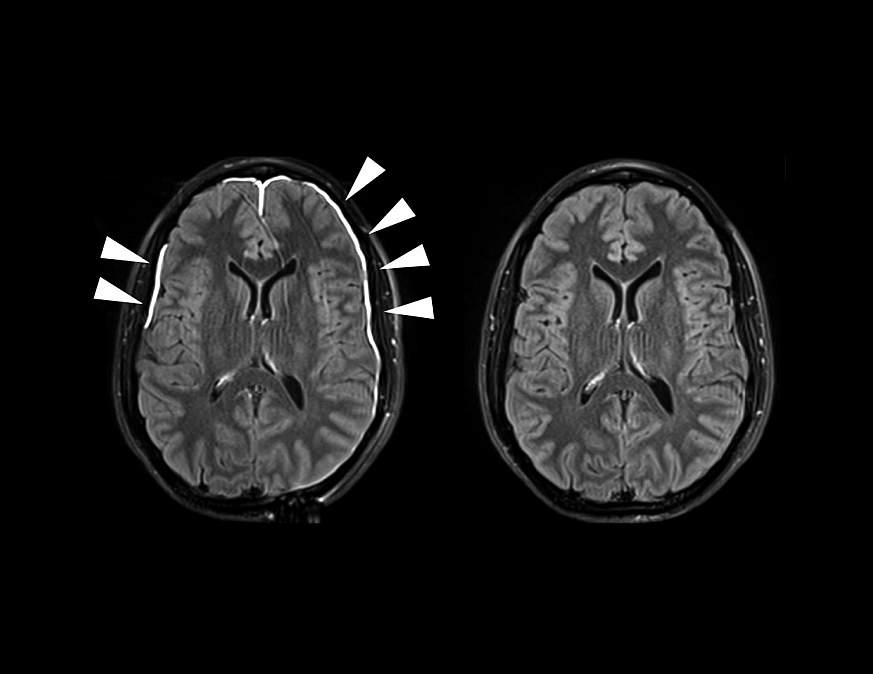

Imaging modalities can be employed to rule out other injuries that may mimic the signs or symptoms of a concussion. In the hospital, a CT scan of the head is the radiographic study of choice for a quick evaluation to exclude neurosurgical emergencies.[12] Clinical decision tools, such as the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) head injury guidelines or the Canadian Head CT Rule, are often utilized to guide the decision about whether head imaging is warranted.[13][14] However, the majority of patients diagnosed with a concussion do not need head imaging.[15] Additionally, a normal head CT does not mean the patient has not suffered a concussion. Further radiographic investigation with an MRI is a consideration in patients with persistent post-concussive symptoms.[16] The role of other imaging modalities, such as functional MRI or PET scan, is primarily for research rather than clinical practice at this time.[17] Testing for serum biomarkers of concussion is still under development but may have a role in future clinical evaluation.[18][19]

If the symptoms are prolonged for more than seven days, consider an MRI, which offers more details.

Two serum biomarkers that show promise include ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase and glial fibrillary acidic protein, which appear to be elevated early in the post-injury phase.

Treatment / Management

After diagnosing a concussion, an outpatient observation by a responsible individual educated on warning signs requiring further evaluation is generally appropriate. Patients with concerning signs or symptoms for more severe head injury may require continued hospital observation. Diagnosis of a concussion should prompt removing a patient from an environment that may lead to a repeat blow to the head (i.e., immediate removal of an athlete from athletic participation).[2]

Treatment of a concussion is primarily supportive. Supportive care of concussion centers around the initial limitation of physical and cognitive activity, followed by a gradual return to previous activity levels. There is no longer a role for extended, strict cognitive and physical rest.[9] While reasonable to encourage rest during the acute post-injury period (i.e., the initial 24 to 48 hours), the patient should then undergo a gradual return to activity. However, there is no known optimal amount of time for the initial rest period.[2] The patient should proceed with a stepwise return to activity with careful monitoring for the return or worsening of symptoms.[2] Recurrence of symptoms warrants a reduction in activity level until symptoms improve. Each increase in activity should generally take at least 24 hours, but again there is no definitive evidence for the optimal timing of a return-to-activity protocol.[2] An athlete diagnosed with a concussion should be forbidden to return to play until cleared by a medical provider.

There is emerging evidence that early, targeted therapies and interventions aimed at specific clinical profiles of a concussion may be beneficial; however, evidence for identifying these clinical profiles and the efficacy of the therapy is still preliminary. Examples of these interventions include vision training for patients with oculomotor dysfunction or cognitive-behavioral therapy for mood disturbances.[9]

Over-the-counter analgesics aimed at controlling headache symptoms are an option, although there is limited evidence as to their efficacy.[16] However, other medications that may alter a patient’s cognitive function, sleep patterns, or mood are not advisable as they may mask symptoms of a concussion. Preventive headache medications should not be initiated after a concussion but can be resumed if the patient was on them before an injury.[20]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis immediately after a head injury should include potentially severe injuries, including cervical spine injury, intracranial hemorrhage, or skull fracture.[11] The differential diagnosis for post-concussive symptoms shifts once outside of the window of the acute injury. Symptoms of a concussion can overlap with other potentially pre-existing chronic conditions such as:[2]

-

Headache disorders or migraines

-

Mental health diagnoses such as anxiety, depression, or post-traumatic stress disorder

-

Problems with attention such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

-

Sleep dysfunction

The clinician must distinguish whether a patient’s symptoms result from a concussion, a product of any other pre-existing conditions, or are of a different etiology.

Staging

Current Guidelines

-

For mild brain injury, imaging studies are not recommended. One should weigh the risks of radiation exposure and sedation in children compared to the benefits of imaging.

-

Use age-appropriate scales to make the diagnosis and make appropriate referrals.

-

Assess risks for the recovery

-

Educate the caregiver/parent on appropriate activity after the injury

-

Parents should encourage the child to return to non-sporting activity gradually after 2 to 3 days.

-

No medication can speed up recovery

Prognosis

The prognosis for a patient with a concussion is usually good, with symptom improvement in the first one to two weeks post-injury. Previous research indicated the recovery timeframe after a concussion was typically about ten days. However, the 5th International Conference on Concussion in Sports recently relaxed the expected recovery timeframe for sports-related concussions, stating that most injured athletes clinically recover within a month.[2] The importance of recognizing a more variable recovery timeline of concussions also received emphasis in a 2013 expert consensus statement.[9] The severity of symptoms within the first few days after a head injury is the most consistent prognostic indicator.[2] At this time, there is no definitive predictor of recovery time from a concussion, and the anticipated recovery timeframe should be individualized for each patient.[9]

Complications

The most commonly seen complication of a concussion is a post-concussion syndrome (PCS) characterized by persistent symptoms lasting weeks to months after the initial injury. The median duration of symptoms in one study was seven months.[21] The transition from a concussion to the post-concussion syndrome is “ill-defined and poorly understood.”[1] Any of the possible concussion symptoms can be present with post-concussion syndrome, but PCS characteristically presents with multiple “somatic, emotional, and cognitive symptoms.”[22][23] The severity of the initial injury does not seem to correlate with the likelihood of developing the post-concussion syndrome.[1] Still, a history of prior concussions does appear to correlate with the likelihood of the development of PCS.[22][21][23]

One of the most feared and concerning complications of a concussion, although rare, is a second-impact syndrome. Second-impact syndrome (SIS) involves a repeat blow or injury to the head before the complete resolution of the initial concussion, resulting in usually rapid, severe swelling of the brain.[24] SIS has the potential for dangerous neurologic complications, including brain herniation and death, though much of the existing data and research on the condition is anecdotal.[24][25]

Research on the long-term consequences of a concussion is still limited. Of greatest concern is the potential for the development of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). This condition is characterized by slow, progressive neurodegeneration due to repeated head trauma and tau protein deposition.[26] Symptoms may include memory disturbances, behavioral or personality changes, and speech or gait abnormalities. The overall incidence and prevalence of CTE are unknown, and at present, CTE can only be definitively diagnosed with a neuropathologic examination.[26] Lastly, research has yet to establish a cause-and-effect relationship between concussions and CTE.[1]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Most concussion patients recover quickly and fully. During recovery, patients need to understand that they may experience a range of symptoms. Some symptoms may appear right away, while others may go unnoticed for hours or even days following the injury, and they may not realize you have problems until they resume their usual activities again. They should be counseled that if they do not return to normal within a week to seek care with a clinician experienced in treating brain injuries. They should not return to sports and recreational activities before consulting with a clinician. Repeat concussions before full recovery of the brain can be very dangerous can increase the chance for long-term problems.

Concussion education should also focus on prevention, such as wearing safety belts and safety seats for children, using helmets for biking, motorcycle riding, skating, etc. The elderly should take extra measures to prevent falls at home.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Management of a concussion requires an interprofessional team approach involving the patient, family members, coaches, therapists, athletic trainers, and medical providers (clinicians, mid-level practitioners, nurses, and pharmacists.)[9] Therapists and neuropsychologists play a crucial role in managing a patient with severe symptoms or post-concussion syndrome.[27][28] In the pediatric population, the involvement of schools and teachers to facilitate the patient’s reintegration into academics is also of great importance.[29] Interprofessional team care can have a positive impact on patient care, as well as resource utilization.[30] [Level 5]

Opportunities for concussion prevention in the general population are limited and largely center around educating patients on the recognition and treatment of concussions. Outside of strategies aimed at preventing falls, there are few options for preventing traumatically induced concussions. Opportunities for preventing sports-related concussions include strict enforcement of the rules of play, promotion of fair play, and reducing the number of contact practices.[1][31] Evidence for the reduction of concussions with the use of specific mouth guards or helmets is limited.[32]

No guidelines exist regarding the disqualification of a patient from athletic participation after a concussion. The American Medical Society for Sports Medicine suggests an individualized approach for each patient and consideration of factors such as persistent symptoms, the number of lifetime concussions, previous prolonged recoveries from a concussion, and the perceived ease of sustaining a repeat concussion when deciding on continued athletic participation.[1]

Review Questions

References

- 1.

-

Harmon KG, Drezner JA, Gammons M, Guskiewicz KM, Halstead M, Herring SA, Kutcher JS, Pana A, Putukian M, Roberts WO. American Medical Society for Sports Medicine position statement: concussion in sport. Br J Sports Med. 2013 Jan;47(1):15-26. [PubMed]

- 2.

-

McCrory P, Meeuwisse WH, Dvořák J, Echemendia RJ, Engebretsen L, Feddermann-Demont N, McCrea M, Makdissi M, Patricios J, Schneider KJ, Sills AK. 5th International Conference on Concussion in Sport (Berlin). Br J Sports Med. 2017 Jun;51(11):837. [PubMed]

- 3.

-

Laker SR. Epidemiology of concussion and mild traumatic brain injury. PM R. 2011 Oct;3(10 Suppl 2):S354-8. [PubMed]

- 4.

-

Lincoln AE, Caswell SV, Almquist JL, Dunn RE, Norris JB, Hinton RY. Trends in concussion incidence in high school sports: a prospective 11-year study. Am J Sports Med. 2011 May;39(5):958-63. [PubMed]

- 5.

-

Barkhoudarian G, Hovda DA, Giza CC. The Molecular Pathophysiology of Concussive Brain Injury – an Update. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2016 May;27(2):373-93. [PubMed]

- 6.

-

Echemendia RJ, Meeuwisse W, McCrory P, Davis GA, Putukian M, Leddy J, Makdissi M, Sullivan SJ, Broglio SP, Raftery M, Schneider K, Kissick J, McCrea M, Dvořák J, Sills AK, Aubry M, Engebretsen L, Loosemore M, Fuller G, Kutcher J, Ellenbogen R, Guskiewicz K, Patricios J, Herring S. The Sport Concussion Assessment Tool 5th Edition (SCAT5): Background and rationale. Br J Sports Med. 2017 Jun;51(11):848-850. [PubMed]

- 7.

-

Ellemberg D, Henry LC, Macciocchi SN, Guskiewicz KM, Broglio SP. Advances in sport concussion assessment: from behavioral to brain imaging measures. J Neurotrauma. 2009 Dec;26(12):2365-82. [PubMed]

- 8.

-

Smits M, Hunink MG, Nederkoorn PJ, Dekker HM, Vos PE, Kool DR, Hofman PA, Twijnstra A, de Haan GG, Tanghe HL, Dippel DW. A history of loss of consciousness or post-traumatic amnesia in minor head injury: “conditio sine qua non” or one of the risk factors? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007 Dec;78(12):1359-64. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.

-

Collins MW, Kontos AP, Okonkwo DO, Almquist J, Bailes J, Barisa M, Bazarian J, Bloom OJ, Brody DL, Cantu R, Cardenas J, Clugston J, Cohen R, Echemendia R, Elbin RJ, Ellenbogen R, Fonseca J, Gioia G, Guskiewicz K, Heyer R, Hotz G, Iverson GL, Jordan B, Manley G, Maroon J, McAllister T, McCrea M, Mucha A, Pieroth E, Podell K, Pombo M, Shetty T, Sills A, Solomon G, Thomas DG, Valovich McLeod TC, Yates T, Zafonte R. Statements of Agreement From the Targeted Evaluation and Active Management (TEAM) Approaches to Treating Concussion Meeting Held in Pittsburgh, October 15-16, 2015. Neurosurgery. 2016 Dec;79(6):912-929. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.

-

Davis GA, Purcell L, Schneider KJ, Yeates KO, Gioia GA, Anderson V, Ellenbogen RG, Echemendia RJ, Makdissi M, Sills A, Iverson GL, Dvořák J, McCrory P, Meeuwisse W, Patricios J, Giza CC, Kutcher JS. The Child Sport Concussion Assessment Tool 5th Edition (Child SCAT5): Background and rationale. Br J Sports Med. 2017 Jun;51(11):859-861.[PubMed]

- 11.

-

Putukian M. Clinical Evaluation of the Concussed Athlete: A View From the Sideline. J Athl Train. 2017 Mar;52(3):236-244. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.

-

Jagoda AS, Bazarian JJ, Bruns JJ, Cantrill SV, Gean AD, Howard PK, Ghajar J, Riggio S, Wright DW, Wears RL, Bakshy A, Burgess P, Wald MM, Whitson RR. Clinical policy: neuroimaging and decisionmaking in adult mild traumatic brain injury in the acute setting. J Emerg Nurs. 2009 Apr;35(2):e5-40. [PubMed]

- 13.

-

Puffenbarger MS, Ahmad FA, Argent M, Gu H, Samson C, Quayle KS, Saito JM. Reduction of Computed Tomography Use for Pediatric Closed Head Injury Evaluation at a Nonpediatric Community Emergency Department. Acad Emerg Med. 2019 Jul;26(7):784-795. [PubMed]

- 14.

-

Bouida W, Marghli S, Souissi S, Ksibi H, Methammem M, Haguiga H, Khedher S, Boubaker H, Beltaief K, Grissa MH, Trimech MN, Kerkeni W, Chebili N, Halila I, Rejeb I, Boukef R, Rekik N, Bouhaja B, Letaief M, Nouira S. Prediction value of the Canadian CT head rule and the New Orleans criteria for positive head CT scan and acute neurosurgical procedures in minor head trauma: a multicenter external validation study. Ann Emerg Med. 2013 May;61(5):521-7.[PubMed]

- 15.

-

Harmon KG, Drezner J, Gammons M, Guskiewicz K, Halstead M, Herring S, Kutcher J, Pana A, Putukian M, Roberts W., American Medical Society for Sports Medicine. American Medical Society for Sports Medicine position statement: concussion in sport. Clin J Sport Med. 2013 Jan;23(1):1-18. [PubMed]

- 16.

-

Halstead ME, Walter KD., Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness. American Academy of Pediatrics. Clinical report–sport-related concussion in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2010 Sep;126(3):597-615. [PubMed]

- 17.

-

Difiori JP, Giza CC. New techniques in concussion imaging. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2010 Jan-Feb;9(1):35-9. [PubMed]

- 18.

-

Asken BM, Bauer RM, DeKosky ST, Houck ZM, Moreno CC, Jaffee MS, Weber AG, Clugston JR. Concussion Biomarkers Assessed in Collegiate Student-Athletes (BASICS) I: Normative study. Neurology. 2018 Dec 04;91(23):e2109-e2122. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.

-

Asken BM, Bauer RM, DeKosky ST, Svingos AM, Hromas G, Boone JK, DuBose DN, Hayes RL, Clugston JR. Concussion BASICS III: Serum biomarker changes following sport-related concussion. Neurology. 2018 Dec 04;91(23):e2133-e2143. [PubMed]

- 20.

-

Meehan WP. Medical therapies for concussion. Clin Sports Med. 2011 Jan;30(1):115-24, ix.[PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.

-

Tator CH, Davis HS, Dufort PA, Tartaglia MC, Davis KD, Ebraheem A, Hiploylee C. Postconcussion syndrome: demographics and predictors in 221 patients. J Neurosurg. 2016 Nov;125(5):1206-1216. [PubMed]

- 22.

- 23.

-

Tator CH, Davis H. The postconcussion syndrome in sports and recreation: clinical features and demography in 138 athletes. Neurosurgery. 2014 Oct;75 Suppl 4:S106-12. [PubMed]

- 24.

-

Bey T, Ostick B. Second impact syndrome. West J Emerg Med. 2009 Feb;10(1):6-10. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.

-

McCrory P, Davis G, Makdissi M. Second impact syndrome or cerebral swelling after sporting head injury. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2012 Jan-Feb;11(1):21-3. [PubMed]

- 26.

-

Mckee AC, Abdolmohammadi B, Stein TD. The neuropathology of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Handb Clin Neurol. 2018;158:297-307. [PubMed]

- 27.

-

Echemendia RJ, Iverson GL, McCrea M, Broshek DK, Gioia GA, Sautter SW, Macciocchi SN, Barr WB. Role of neuropsychologists in the evaluation and management of sport-related concussion: an inter-organization position statement. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2012 Jan;27(1):119-22. [PubMed]

- 28.

-

Ellis MJ, Leddy J, Willer B. Multi-Disciplinary Management of Athletes with Post-Concussion Syndrome: An Evolving Pathophysiological Approach. Front Neurol. 2016;7:136. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.

-

Purcell LK, Davis GA, Gioia GA. What factors must be considered in ‘return to school’ following concussion and what strategies or accommodations should be followed? A systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2019 Feb;53(4):250. [PubMed]

- 30.

-

Wilkins SA, Shannon CN, Brown ST, Vance EH, Ferguson D, Gran K, Crowther M, Wellons JC, Johnston JM. Establishment of a multidisciplinary concussion program: impact of standardization on patient care and resource utilization. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2014 Jan;13(1):82-9. [PubMed]

- 31.

-

Emery CA, Black AM, Kolstad A, Martinez G, Nettel-Aguirre A, Engebretsen L, Johnston K, Kissick J, Maddocks D, Tator C, Aubry M, Dvořák J, Nagahiro S, Schneider K. What strategies can be used to effectively reduce the risk of concussion in sport? A systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2017 Jun;51(12):978-984. [PubMed]

- 32.

-

Daneshvar DH, Baugh CM, Nowinski CJ, McKee AC, Stern RA, Cantu RC. Helmets and mouth guards: the role of personal equipment in preventing sport-related concussions. Clin Sports Med. 2011 Jan;30(1):145-63, x. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

-

Disclosure: Benjamin Ferry declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

-

Disclosure: Alexei DeCastro declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

Original Article – https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537017/